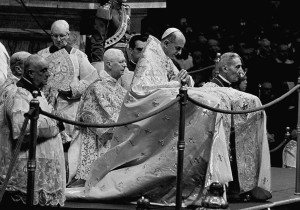

The bottom line in the spirituality of a person seeking God is to discover how to live ever more fully one’s unique relationship with the God that creates him/her. At the ecumenical council, Vatican II during 4 years the 2500 bishops of the Catholic Church percolated on behalf of their charges a new, more pastoral approach to this goal, fitted to modern times. They poured over the myriad paths, most without a name, found in created history during centuries past and through their own contemporary experience. This openness to all the world in time and space in terms of other and different paths to God has signified the surrender of the traditional Christian monopoly on grace, and has turned out to be one of the Council’s underlying values that surfaced in the final document on God’s revelation to humankind (Verbum Dei). For me as a third generation Catholic, however, the Church set the general parameters for my initial spiritual journey. Like many others I received my map to find God, prepared uniquely for me supposedly by the universal Cartographer, but whose guideposts, orientations, and justifications had been handed down over two millennia wrapped securely in the spiritual wanderings of a joint political and religious culture.

Before the Council two values ruled the bottom line or the final destination for a life in the Spirit. The first, holiness was the goal and it was conceived as essentially linked to the verb, achieve. Union with God along with how strictly you could keep given rules measured holiness. St. John Berchmans, a Belgian Jesuit novice, held up as a model for keeping his eyes under strict control, was said to never have seen the decorative design of the ceiling. Holiness would receive its corresponding reward in heaven dependent on how high you had climbed the spiritual mountain here on earth. Within the boundaries of your status in life if you worked hard enough, (God’s grace would always to available to second your efforts) you could interpret the signposts that reassured you of your progress.

Second, holiness ostensibly concretized in the imitation of Christ had to be worked out within the established system, the example of Christ himself, that is, as interpreted and fostered by the politico-religious Catholic Church. Spiritual goals were achieved through successive “approved” models of asceticism that succeeded the high point of martyrdom. Approved withdrawals from worldly influences corresponded to a prevailing socio-economic culture of the period, sometimes modified by geographic location, retreat into the dessert, separation from the world into the monasteries or priories, pilgrimages to holy shrines, travel with the Crusades, missionary work spreading the Gospel, continued up to our own day through a plethora of religious associations and groups. The predominate spiritual climate could be characterized as a semi-competitive athletic asceticism.

In the Catholic Church where my initial spiritual goals were defined before Vatican II, the link between Christ and how to imitate him had been canonized by Church leadership through the system of recognizing official models to be imitated as his “heroic” followers. As the Church grew over 1500 years in its political and religious role two culturally enshrined virtues, obedience and asceticism, normally packaged the criteria accepted by the “official” interpreters of Christ’s example. Dissident initiatives were handled by the then accepted means of repression. Even the mind’s or intellectual obedience was demanded when the Church and its multiple institutional delegates spoke. As a backdrop cultural value obedience shored up the authority base of the Church’s leadership “to command in God’s name” was much more pervasive than its overt political role would suggest. On the other hand asctical practices, encouraged and embraced by the expiation rationale for the Cross and abetted by a dualistic understanding of a flawed human nature, gave free rein to a holy war on many wonderful human qualities. The spiritual approach of the Catholic and other Christian denominations have left serious scares on our created human psyche affecting entire countries for generations.

Vatican II, on the other hand, called to a mission of aggiornamento, or catching up on modern knowledge, promulgated the vision of God’s communication of itself to humankind through a continuous act of creation whose culminating point has been the human person of Jesus and his message. The opening of the Council to the validity of historical research reveals his message to be a passionate invitation to accept God as his own and the father of all (The Our Father). This notion of God is seen as a backdrop to the acts and proceedings of the Council insofar as an interactive exchange with God on the part of the human family, individuals and communal institutions, the stuff of a relationship, would galvanize the Church’s newly adopted mission to the world.

As individuals and members of simple and complex human institutions we are witnesses in history and contemporary affairs to the physical and cultural deficiencies of the human family as it struggles to realize Jesus’ vision of his father’s reign (kingdom). Complex technological tasks and seemingly insuperable problems face our present global village. As created members of the human family we all have some contribution to our space however limited it may be. Vatican II has reemphasized for us that a faith in Jesus as a divine and bone fide member of our created family sets the table for a relationship with God, our Creator, father and mother and much more, to accompany us in defining and living our individual and collective roles in its reign.

It is not easy to encounter the infinite, unknowable OTHER as our companion and guide on this journey. What do we discover behind the door opened after many centuries by Vatican II to Jesus’ way to his father? Portraying the human face of God on earth his humble way calls us to imitate his passionate search for intimacy with his father to find in ourselves and the space created for us our unique path to God itself and our work to bring about its reign.

Jesus finds his father’s presence reflected in all of creation that teaches many spiritual lessons. In the Our Father our work on earth, “as it is in heaven” refers to our hallowing God’s name as a preparation for harmonizing our contribution to the human family. In God’s created world no one stands or falls alone. In a revolutionary stance against a fierce social patriarchal bias women and children before God are put on the same level with men. Jesus courts the hoi polloi, the rejected and marginalized by society. All are to receive respect by members of a human family which as clay in God’s hands is in the process of becoming more in line with the teachings of God’s reign. God is infinitely personal in knowing and loving his work reaching into the depths of our souls to unmask the darkest demons, stages to be surpassed through an exchange with God in our evolutionary march to fullness. Among the words of the gospels that the specialists ascribe to Jesus as probable there is virtually no mention of sin but only of temptation, a necessary step in the process of moving forward.

Finally, and most important for our life in the Spirit, is our response in love seeking intimacy with the giving, unconditional love of Jesus’ father. In practice this means living an unshakable trust despite whatever turn, crook, or obstacle comes up in our ongoing interchange with God, including inevitable falls, and even sin. Jesus is always our guide, up to his ultimate, horrific death on the cross, not to atone for many failures and sins on humanity’s long road, but to prove to us by example his absolute trust in the message of our redemptive growth assured by his father God.